Spectacular Spirals¶

This project uses turtle graphics to draw spirals: choose your own design. On the way, we meet a spiral that is 200 million years old.

First take your polygon¶

Start the project by making an empty file spiral.py.

Right-click and open it with IDLE.

Type this (or copy most of it from final.py in the introduction) and save it:

from turtle import *

speed("fastest")

def polygon(a, n):

"n-sided polygon, side a."

for i in range(n):

forward(a)

left(360/n)

The new line is called a documentation string,

a little reminder of what the function does.

It makes no difference to what the code does,

but in IDLE,

when you get as far as typing polygon(,

IDLE will pop up this string as a reminder.

Important

Never throw code away.

In these projects we explain the program a piece at a time. Mostly you should add each new code fragment to the program you have already, normally at the end. Sometimes the fragments show a change to what you have.

Occasionally, there is a short fragment of code that you only need for a few tests, then you’ll replace it.

If ever you want to delete a lot of code,

first use “File” >> “Save Copy As” and give a name like spiral_2.py,

so you can go back to your program as it was.

Offset and fill the polygon¶

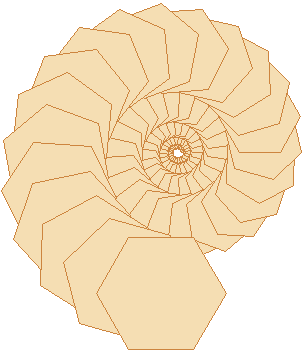

Your program is going to draw lots of different spirals. Here’s a simple example where you can see what’s going on:

Drawing starts with the smallest square tile, nearest the middle, and continues anti-clockwise, putting down tiles.

Each tile is slightly bigger than the last. Each circuit has the same number of tiles, that you choose, 9 in this case. By the time it gets round once, the tile is twice the original size, and twice as far from the centre. It will go round as many times as you choose.

You will draw each tile with your polygon method.

To put it in the right place,

suppose the turtle is in the centre, and pointing the right way.

We need to go forward some distance, then draw the polygon.

Then we go back to the centre, ready for next time.

In code, it looks like this:

def tile(r, a, n):

"n-sided polygon, side a, at range r (assumes pen is up)."

forward(r)

pendown()

begin_fill()

polygon(a, n)

end_fill()

penup()

back(r)

Add that at the end of your program, and then add this to test it:

# Test

fillcolor("red")

tile(100, 50, 6)

Lines that begin with a # are comments.

Python ignores them: they’re a hint to the humans.

You should put comments in code you invent,

but you don’t have to copy them in these examples.

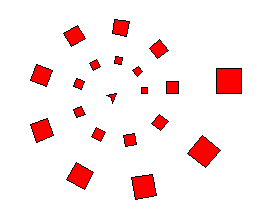

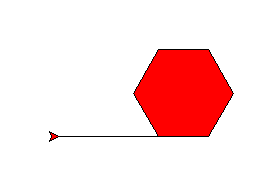

Save and run that. It should look like this:

The initial line is not a fault: it is there because we started with the pen down.

Turn and repeat¶

Putting the tiles down in a spiral is still too difficult for us in one leap. Think instead how would we put tiles down in a circle.

That would be rather like drawing a polygon,

except we use the tile function each time

instead of forward.

Add after your last function:

def circ(r, scale, n, tiles):

"Circle of n-sided polygons at radius r and size r/scale."

# Angle between each tile

step = 360 / tiles

# Now draw it

penup()

for i in range(tiles):

tile(r, r/scale, n)

left(step)

Change your test code at the end to read:

# Test

fillcolor("red")

circ(100, 10, 4, 9)

Save and run: you should get a circle of 9 little squares.

Grow a little each time¶

How can we turn the circle into a spiral? This means making the distance from home (the radius) and the tile size grow each time a tile is placed.

Here “grow” means that we should multiply the size and the radius by some amount each time we put down a tile. The growth factor should be only a little more than one, or the size will get huge in just a few tiles. Remember what happens to powers of numbers from chapter 1?

We have to work out the starting radius and the growth per tile. Choosing that number, a little bigger than one, to get the final size you want, is the the hardest part. You may not have learned the maths for this yet, but the comments explain what’s happening. Add after your last function:

def spiral(r, n, scale, cycles, m, growth):

"""Spiral of n-sided polygons out to radius r and size r/scale,

in given number of cycles of m steps, growing each cycle.

"""

# Angle between each tile

step = 360 / m

# Total number of tiles (made a whole number)

p = int(cycles*m) + 1

# Growth between each tile

g = growth ** (1/m)

# Starting radius (this will grow with each tile placed)

r = r / (growth**cycles)

# Now draw it

penup()

for i in range(p):

# As the distance from the centre grows, so does the polygon

tile(r, r/scale, n)

left(step)

r = r * g

You can see this is like the circ function,

but with extra code to make the size change.

Finally, we’re ready to try this out.

At the end of your program, add:

def example():

fillcolor("red")

spiral(100, 4, 4, 2, 9, 2)

The call to spiral has a lot or arguments.

In order it says that you want:

- a final size of 100.

- squares (4 sides)

- … that are 4 times smaller than the distance from the centre

- to go round twice

- to have 9 tiles per revolution

- to grow by a factor 2 each revolution

Save and run this. Then at the shell prompt type:

>>> example()

You should get the example we showed earlier.

Choose wild numbers¶

Here is a suggestion to add:

def ammonite():

pensize(1)

color("peru", "wheat")

spiral(100, 6, 3/2, 4.7, 22.5, 2)

hideturtle()

And here is another a suggestion to add:

def vortex():

pensize(5)

color("navy blue", "royal blue")

spiral(500, 6, 3, 15, 4.2, 1.4)

hideturtle()

Call them at the shell prompt, like you did with example().

The function call reset() will clear the drawing window between tests.

In the vortex you get a sort of two-way spiral

because the number of tiles per cycle is not a whole number,

but is close to a whole number (4.2).

So what might have been 4 straight lines becomes 4 curved lines.

What number would make them curve the other way?

Try calling spiral in your own function with a variety of numbers.

If you find a combination you like, give it a new name.